Striking images of Iranian protesters cutting their hair drew the world's attention to the arrest and custodial death of Mahsa Amini, 22 and to the systemic oppression in Iran. The act is a political expression of their grief, rage, and defiance. People around the world are doing the same to express their solidarity.

In the sixties and seventies, civil rights activists refused to straighten their hair to reject assimilation and to say "accept Black hair as it is". Afros were the Black Panther party's rejection of White beauty aesthetics.

"Our hair was a physical manifestation of our rebellion," Lori L. Tharps, coauthor of Hair Story: Untangling the Roots of Black Hair in America. More recently, the "Back to Natural" movement is tied to appreciating Black hair for its uniqueness and beauty, and not necessarily for advancing a political cause. (Source: The radical politics behind Afros. André NaquianWheeler in i-d vice.com)

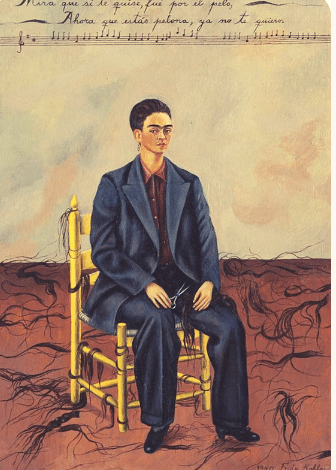

Hippies wore long hair as a sign of freedom from mainstream society and to protest against the Vietnam war. Frida Kahlo made a self-portrait where she is holding a pair of scissors, her hair is cropped short, and thick strands are scattered all over. The lyrics of a song are written at the top saying, "Look, if I loved you it was for your hair. Now that you are without hair, I don't love you."

This work has been interpreted as Kahlo's declaration of independence and the rejection of certain idea of femininity and also her partner Diego who caused her much torment. Hair and emotion are interlinked.

Rose McGowan who started the hashtag "MeToo" wrote in her memoir Brave that she got a buzz cut because she no longer wanted to look like a “fantasy fuck toy". McGowan said she no longer wanted to conform to Hollywood and cutting her hair helped her feel liberated and less commodified—"powerful and cold." Russian artist & political activist Nadya Tolokonnikova, the founding member of the group Pussy Riot, reportedly dyed her hair partially green to match the Russian prison uniform she wore, protesting on behalf of incarcerated women. Fantasy hair colour is worn by many as a rejection of norms.

“Hair has been used as an expression of politics and personal beliefs since the earliest times, and we see examples of it time and again in diverse cultures across the globe", says hair historian Rachael Gibson. "Hair can be a literal canvas for political beliefs." (Source: How Hair Became a Form of Political Expression. Ellen Burney. Vogue.au)

The length of hair some gender non-conforming people choose sends a clear message regarding their gender-fluidity.

"There is a certain paradox about protest hair, in that its power comes from the stigma it fights," writes Therese Marie Lim. "Protest hair will only become moot when there is a complete and total rejection of the gender norms that are attached to women’s hair. And because that hasn’t happened yet, any violation of that norm becomes a statement." (Source: 'Why Hair Is A Potent Act Of Defiance' by Marie Lim in thebeaulife.co)

During witch-hunts in India, women's hair is cut or shaved as hair is associated with dignity and pride. Forcing Sikh people to cut their hair is religious persecution. Rituals that strip Hindu widows of their sexuality and social status include the shaving of hair.

Our hair is entwined with many things: health, sexuality, celibacy, desirability, gender, bodily integrity, social status.Some children resist their first haircut. Most adults are conscious about how their hair looks. Balding due to genetic reasons, ageing, disease, or medical treatment can cause significant distress. Greying hair is not easy for everyone to accept. Ableist, ageist, beauty, and gender norms complicate our relationship to our hair—a crucial part of our identity.

In the "baccha posh" tradition in Afghanistan, children assigned female at birth are brought up as boys. This allows them to access education and the freedom boys have in Afghanistan. Gender politics can be manoeuvred via how hair is worn.

In 1915, famous ballroom dancer, Irene Castle, cut her hair short just before a surgery for appendicitis. The bob ended up becoming a trend and a statement of social rebellion. (Source: The Bob: A Revolutionary And Empowering Hairstyle. Karen Harris in The History Daily)

In the 18th century, Marie-Antoinette (who was of Austrian origin) donned elaborate hairstylesto make her body appear more French, explains Desmond Hosford in The Queen's Hair: Marie-Antoinette, Politics, and DNA. Antoinette’s hair was a sort of palette for power: one hairstyle even featured a model ship to celebrate a French naval victory. Later, it suddenly turned white, presumably as a result of the persecution she had to face. (Source: The Political Power of Marie Antoinette’s Hair in Daily Jstor)

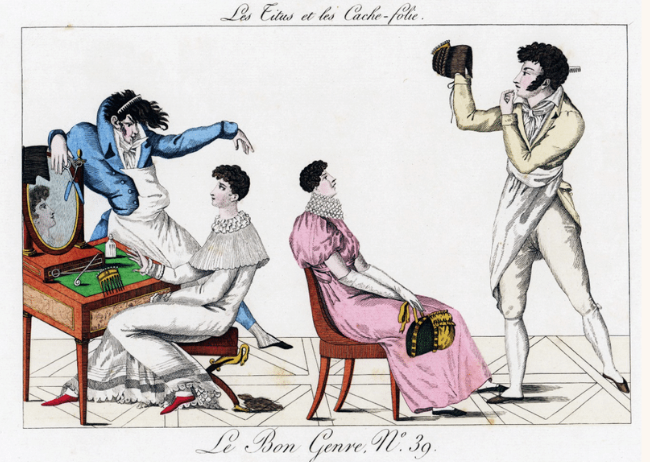

At bals à la victime (victims’ balls), children of executed French aristocrats danced in bizarre revelry. Both men and women chopped their hair close to the nape of the neck. It was a nod to victims of the French guillotine whose hair was shorn before execution. Some even wore red scarves around their neck, a gory symbol of the fatal slice. (Source: Stephanie Buck. Soulbellystories.com)

Hair has always been charged with political and emotive meaning for people with very different motives.