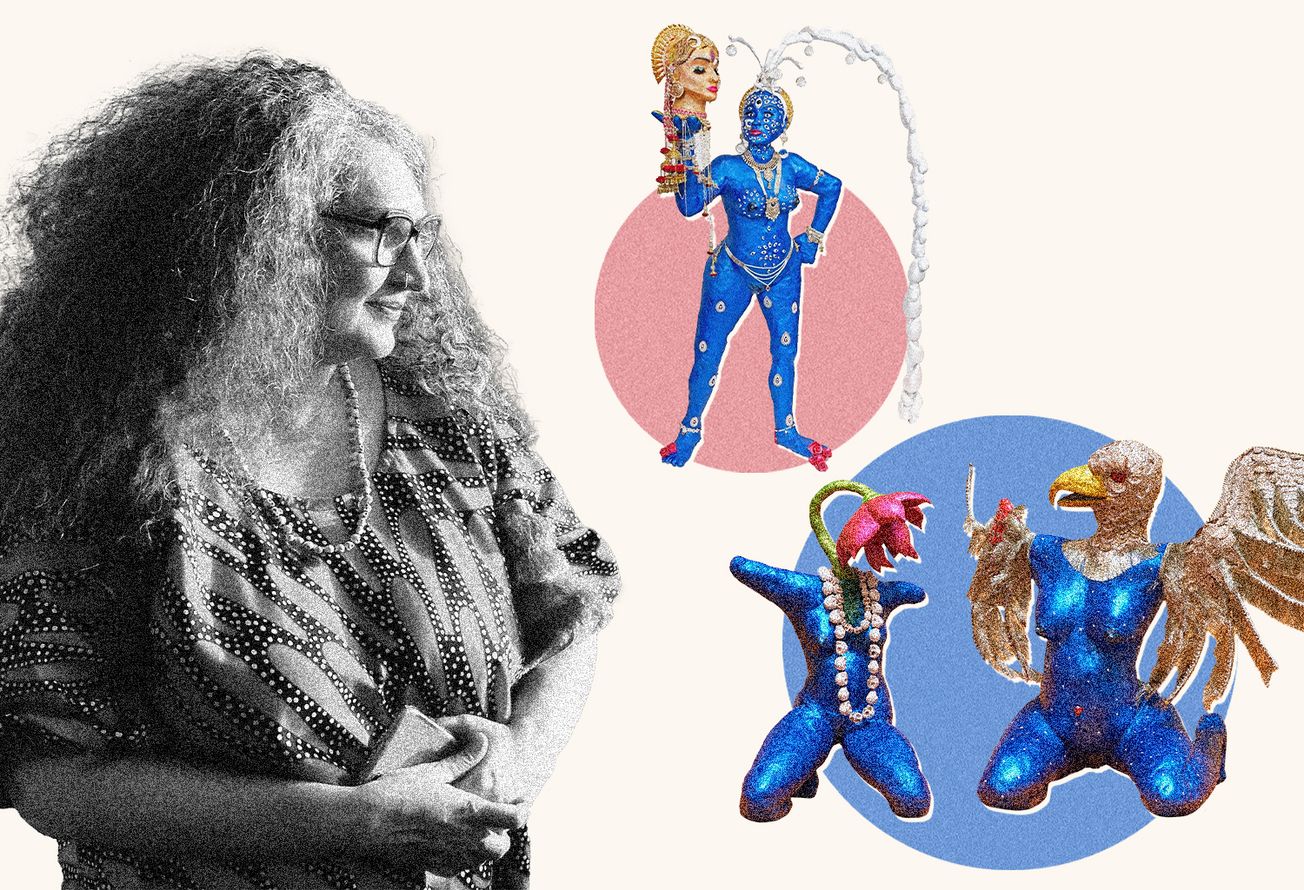

Jaishri's vivid art is fiercely feminist. It frequently draws on mythology and is always steeped in the political. Her yoniverse, as she calls it, is populated with clay figurines, some bearing resemblance to Harrapan sculptures, others to temple goddesses—all furiously opposed to Brahmanical patriarchy. Jaishri deftly plays with scale: her minuscule "taliswomen" are endearing and replete with feminist energy, whereas her human-sized "feminist goddesses" and misogynist demons relay intense emotions whilst making bold statements. Jaishri's Jasmine Blooms At Night is a series of sculptural and painted portraits of South Asian feminists driving change—people Jaishri has interacted with and extends her solidarity to.

Smashboard's Noopur Tiwari met with Jaishri in her studio in the summer of 2022. Here is a summarised version of their chat.

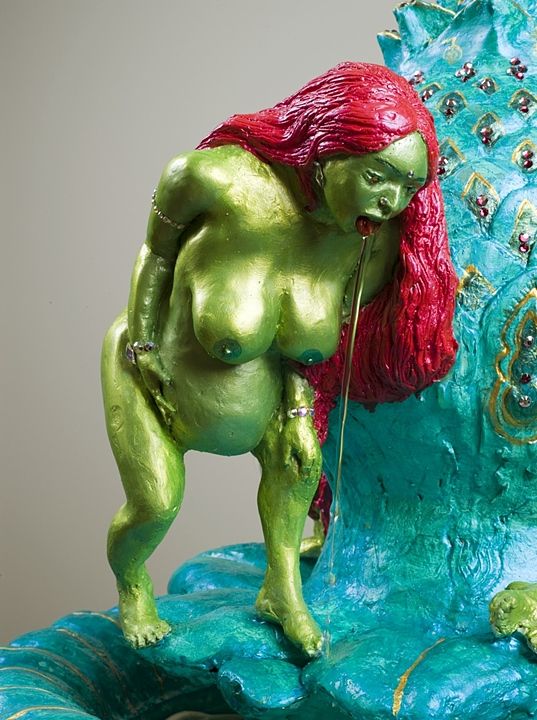

Noopur: I see a human figure with the lower half shaped like a yoni. She has three pairs of breasts and six children feeding off of them. It's animalistic?

Jaishri: Yeah, like kittens or puppies, you know. And this is how I feel about motherhood. This one is based on my kid's kindergarten teacher, Mrs Ham, who was very pink and constantly surrounded by her four children. As a feminist, I couldn't understand that type of existence because she had to be mothering them and taking care of them all the time.

Noopur: In the bigger version of the sculpture, there is an umbilical cord going around the neck of the woman.

Jaishri: I've seen so many women strangle themselves in the desire for motherhood without understanding the implications of it and what an intense and difficult thing it is actually to be a mother. The sculptures reflect my own conflicted relationship with my mother, how I was super conflicted about becoming one, all of those things. They become receptacles for very contemporary issues and dialogues.

Noopur: The figures in your sculptures almost always have breasts, a vulva or a yoni.

Jaishri: Yes, but this one (photo above) has a penis and breasts. I've just been in community with queer people forever. So queerness has been part of my life and my work. I may not be with women now, but there was a time when I was, and that's always how I identify, regardless of where I am now.

So this one (photo above) is called Endgame. And it has multiple narratives. The larger meta-narrative is, as you can see, this beast is several beings. Human and animal. And so it's a metaphor for climate change and us being on the precipice. That's Mother Earth. And that's us. Taking all the other species down where it does, right and like an endgame, because this is it, you know, nothing will survive climate change. Right. And that's one. And then it's the USA and Trump, India and Modi. And then it's like, my mother and I, it's internal demons, you know? It's a lot of different stories.

Noopur: And she is stamping on a lotus

Jaishri: This one is called Kamala's Inheritance. And so this came together after Joe Biden won and Kamala became vice president. And she's not someone I supported because of her centrist policies, and her carceral kind of feminism is very, very, very problematic to me. She never speaks up against the BJP or anything; she's completely silent. So this is about that. The blue Lajja Gauri, with the lotus, is like a head bent in shame for being co-opted. Right. And so, in the larger galleries, Lotus' head is bent, and she's put together with an amputated Kali with her skulls because that is the whole legacy.

Noopur: This figure that's unable to fly is the eagle, the American eagle. Why is its right wing broken and bloody?

Jaishri: You know, because this is the right wing. It's like the Republican sabotaging democracy in the country, or for their agenda, literally crippling the country and bringing it to its knees, you know? It was called Kamala’s Inheritance because it's as much about what she inherits as it's about what she's complicit in. She talks about being from a family of like freedom fighters. Still, she doesn't speak at all about the caste supremacy of Tamil Brahmins that brought her mom here in the first place. It's a very careful positioning that she occupies.

Noopur: Also, I suppose electoral democracy functions like that, right? In the sense that the state-corporate nexus is something which is the bedrock of electoral democracy today, which excludes all of us. Tell us about this one: Myself, daughter of Indra, granddaughter of Ganga, which is in human size.

Jaishri: It's the most personal and ridden with metaphors. The feminist personal is political. And so it's about cutting myself off from a legacy of a toxic kind of patriarchy through the hands of women. It's about detachment or severing from intergenerational trauma. At the same time, it is about what my mother would ask of me—to give up myself to please her internalised sexist ideas of perfection.

My mother's name is Indra—there is the fable of how the God Indira gets cursed with a 1000 vulvas that subsequently get turned into eyes. My mother is a Gemini so her figure is covered with multiple eyes that are ritually affixed to deities on the front, and the vulvas are on the back. This blue figure with multiple eyes is holding my severed head which had a vulva for a third eye.

The third eye is in the form of a vulva because of how she saw me. When I was 22, my mother said that my parents would pay for my pubic hair to be surgically implanted on my eyebrow to help with my vitiligo and "help me find a better husband". I have struggled to get her to see me as an autonomous person all my life. Her need to control and project on me was overwhelming.

All of the eyes in the sculpture are looking. They are projections or her gaze on me. And then my grandmother's name was Ganga. So she's on the top of the head of my mother, with water emerging from the large blue figure as it would traditionally be shown as flowing from Shiva’s locks. My grandmother was super mean. And so Kali's tongue is out as a gesture to all the women who serve as vehicles of patriarchy.

Noopur: I get the sense that you haven't really incarnated Kali in your sculptures, but you have reappropriated the goddess energy and monster metaphor.

Jaishri: Yes. Within the sculptures, there are two impulses. There's the very queer impulse with all the queer and trans bodies, and then there's the super fierce feminist critique of Hinduism, nationalism, and environmental politics. There is a whole resistance to patriarchal forms of oppression.

Noopur: Historically, art created by women has often been stereotyped as very physical, bodily, or organic. Many excellent feminist artists didn't get any recognition, whilst their contemporaries who were assigned male at birth flourished and became well-known. As an artist pitted against the patriarchal, corporate, and capitalist art world, how do you balance being an artist who needs to sell and whose art needs to be feminist? People who have the money to buy your art must also be the ones who feel threatened by the work that you do. It's a typical feminist dilemma, I guess.

Jaishri: I have no solutions. I'm fucking trying to figure out how to pay beyond the next four months. All I can hope and pray for is that the work continues to get stronger and becomes so compelling that people cannot ignore it anymore. But you're absolutely correct in identifying the resistance. It's challenging.

The few collectors I know who have the kind of money to write me big cheques are White. So, they're disengaged from the kind of South Asian politics that you and I are steeped in. Most South Asian collectors are super threatened by this work because they don't want art that is critiquing India and Hindutva or [is] feminist to this degree as it's a hard thing for them to put in their homes. But I can't turn down the level of critique.

Noopur: Yeah. That would be taking the meaning of your work away.

Jaishri: Yes. And you and I know that the work needs to be seen by the public and doesn't necessarily need to be owned by private individuals. It needs to be owned by public institutions and museums. And it needs to be accessible to everybody. Because that's what I'm making it for.

Noopur: And what gives you the impulse to keep going on?

Jaishri: You can't stop because it's not even you making the work. The work needs to be made. I believe in its power to create social change because I witness it every time someone encounters the work or responds to a talk I give. And of all the things I can do to create social justice, this is the thing that gives me the most pleasure and joy in life.