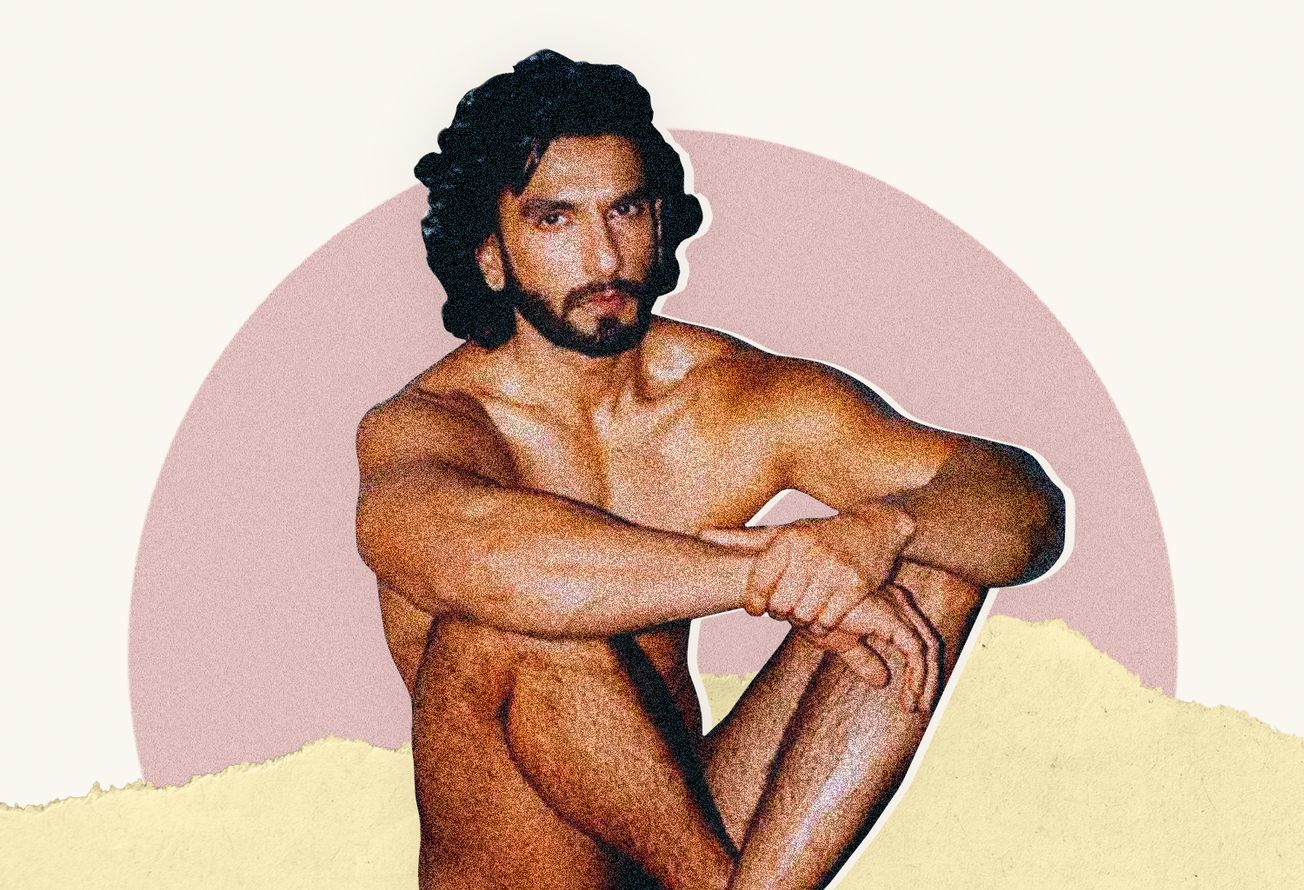

Bollywood actor Ranveer Singh’s nude photos have led to much talk about the “female gaze” which is often misinterpreted as the mere reversal of the “male gaze”—objectifying men instead of women. Let’s bring some feminist clarity to this whole “gaze” issue.

A Reminder: What is the “Male Gaze”?

The term was coined in 1973 by feminist scholar and critic Laura Mulvey who wrote about “woman as image, man as bearer of the look”.

“In a world ordered by sexual imbalance, pleasure in looking has been split between active/male and passive/female. The determining male gaze projects its fantasy onto the female figure, which is styled accordingly. In their traditional exhibitionist role, women are simultaneously looked at and displayed, with their appearance coded for strong visual and erotic impact so that they can be said to connote to-be-looked-at-ness”.¹

Why is the “Female Gaze” not just the “Male Gaze” Reversed?

The female gaze (we prefer the “feminist gaze”) is not the reverse objectification of men by women but a critique of the power dynamic inherent in the act of looking and being looked at. In a keynote address (full of humour and judicious reflection), non-binary filmmaker Joey Soloway (creator of the series Transparent, among others) spoke about the “female gaze” as daring to return the gaze. It says, “We see you, seeing us!” It is a way of seeing that “puts us back into our bodies”. Soloway speaks about a state of feeling embodied and connected as subjects through the female gaze. This is the opposite of the male gaze that reduces us to disembodied objects.²

They (Soloway) define art and culture as propaganda for the self or “protagonism”—a way to get the audience on the protagonist’s side. This protagonist is usually a white, cishet man in world cinema. He is “a privilege generator”. (Soloway doesn’t say this, but in India, it would be a Savarna cishet man).

How the Male Gaze Hurts Women

The male gaze is far from benign. Women’s self-worth, their value and social mobility, as well as their access to dignity and material resources, are defined by how men see them.

Visuals we see around us are social mirrors that shape our sense of self. Films, social media content and advertising turn into powerful tools of social engineering. They idealise, humanise, and dehumanise us based on market dynamics. This tends to impact how women and marginalized folks construct their sense of self.

The mere anticipation of the male gaze leads women to self-objectify and this has a detrimental impact on their mental health and can lead to fragmented attention, anxiety, dysphoria, etc.³

The ubiquitous nature of male fantasies is such that even women can only view themselves as catering to them.

“Male fantasies, male fantasies, is everything run by male fantasies? Up on a pedestal or down on your knees, it’s all a male fantasy: that you’re strong enough to take what they dish out, or else too weak to do anything about it. Even pretending you aren’t catering to male fantasies is a male fantasy: pretending you’re unseen, pretending you have a life of your own, that you can wash your feet and comb your hair unconscious of the ever-present watcher peering through the keyhole, peering through the keyhole in your own head, if nowhere else. You are a woman with a man inside watching a woman. You are your own voyeur.”— Margaret Atwood⁴

Reclaiming the Gaze

There are repeated attempts to reclaim the gaze. Director Céline Sciamma says her film Portrait of Lady on Fire (2019) is a “manifesto around female gaze”.⁵ An aristocratic young woman called Héloïse is about to marry a nobleman. Artists are commissioned to paint her portrait. However, Héloïse, who doesn’t want to get married, makes things difficult for several portrait-artists as she refuses to let them use her as an object to be looked at by her husband-to-be.

Only one artist, Marianne, succeeds in finishing the portrait, by accepting the reciprocal gaze of her subject (“I see you seeing me”). Marianne destroys a version of the portrait that Heloise thinks doesn't capture her true essence. Sciamma says “when you look at somebody, they are also always looking at you”. That is why it’s important that the story is about two women so there is no gender domination, no intellectual domination, and no social hierarchy.

The female gaze looks deep enough to feel impacted by the subject rather than merely consume her as the subject of cishet male fantasy. It is fundamentally different from the self-serving “looking at” to control and abuse without “being looked at” (as in state or corporate surveillance).

The concept of the “male vs female gaze” extends away from the gender binary to include BIPOC, Dalit, Adivasi, Muslim, and other communities who are historically “othered” by cultural narratives. Therefore, we now have the “White gaze”, “Cis gaze”, and “Savarna gaze”.

Can queer women objectify other women?

Does all of this mean queer people can’t openly admire sexually attractive images of other women? Not quite. Sexual objectification dehumanises women and reduces them to nothing but sexual objects to be exploited by men. Sexual attraction is about feeling desire towards a person and also respecting them as human beings.⁶

Is there a risk that Ranveer can get objectified?

So, do women who lecherously admire Ranveer’s nudes run the risk of objectifying him? It’s a bit like asking if “reverse racism” is possible. Systemic patriarchy means women can’t objectify Ranveer or any other cis man in the way in which men objectify women because rape culture and sexist structures don’t oppress cis men.

SOURCES:

¹ Laura Mulvey, Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, Screen, (Written in 1973; Published 1975). Volume 16, Issue 3, Autumn 1975, Pages 6–18

² TIFF: Master Class - Jill Soloway [September 11th, 2016] (available on YouTube)

³ Calogero, Rachel M. “A Test of Objectification Theory: The Effect of the Male Gaze on Appearance Concerns in College Women.” Psychology of Women Quarterly 28, no. 1 (March 2004): 16–21.

⁴ Atwood, Margaret, The Robber Bride, Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1993.

⁵ TIFF: Céline Sciamma on the Female Gaze in Portrait of a Lady on Fire [January 30, 2020] (available on YouTube)

⁶ M Slade, Am I a Queer Woman Looking Through the Male Gaze?, Everyday Feminism, 22nd July 2017

This article was first published as a social media post here