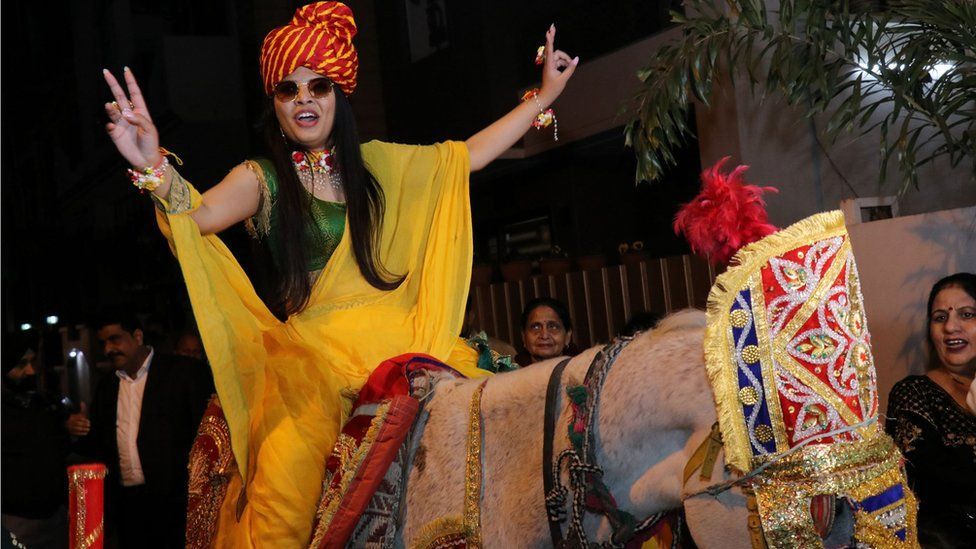

Indian weddings are no longer just private events. Central to a fifty billion dollar wedding industry, they have turned into spectacles that are all about posturing. Celebrity and influencer weddings dominate social media trends and news headlines. In February, a bride in Ambala led her baraat on a horse instead of the groom. Her story went viral and even made it to news reports. A “wedding expert” told the BBC that this was a feminist statement and that making grand entries is something Indian brides do now. “[T]hey come with flower girls, or surrounded by girls carrying lamps, they come in a limousine or in buggies or chariots bedecked with flowers.” Last year, another wedding story went viral when a celebrity couple applied sindoor on each other's foreheads instead of just the groom applying it on the bride’s.

These stories are presented to us as inspirational—brides breaking free of traditions, heralding change and smashing the patriarchy. We are now in the era of the girlboss bride. Picture a woman in a wedding lehenga, donning a pair of sunglasses. You might recall the hit Bollywood number Kala Chashma (in Baar Baar Dekho, 2018), where Katrina Kaif was the bride in aviators. The sunglass trend picked momentum. For his 2019 catalogue, Sabyasachi, the most prominent luxury bridal wear designer, presented the bride in rose-tinted glasses.

Unlike the traditional Indian bride, who is supposed to be demure or veiled– sometimes beyond recognition–the girlboss is bold and unorthodox. She flaunts her sexuality; she makes sure she is seen and heard. Quitting her parental home for her husband’s is not a moment of grief but celebration. This laughing, boisterous bride makes for a refreshing image. It would certainly not hurt to have more like her. But alas, she can only be found among a few, mostly those with both wealth and caste privilege.

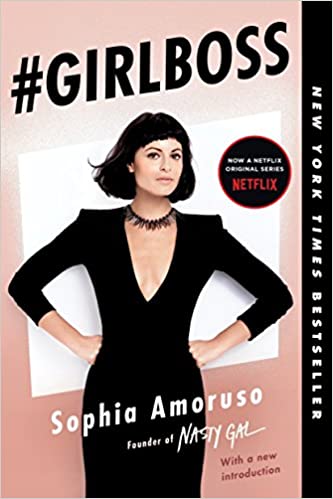

The “girlboss” made it into our cultural lexicon thanks to Sophia Amoruso, the owner of a fashion retail brand called “Nasty Gal”. Amoruso wrote her autobiography #GIRLBOSS in 2014. Here's how she describes it:

“#GIRLBOSS is a feminist book, and Nasty Gal is a feminist company in the sense that I encourage you, as a girl, to be whom you want and do what you want. But I’m not here calling us “womyn” and blaming men for any of my struggles along the way.”

From its inception until now, the concept has been about creating a personal brand of empowerment. Accessible only to the wealthy and symptomatic of hustle culture and its false promises of endless rewards for merit and hard work. The girlboss is too busy wielding corporate office power, too focused on amassing wealth, and too oblivious to the existence of real structural inequalities. She demeans herself by embracing the infantilising “girl” tag, refusing to be called a woman. An essential aspect of being a girlboss is also letting people know, loudly and clearly, what makes you one. How good an idea is it to elevate this insidiously anti-feminist worldview as inspirational?

There’s something deeply deceptive about the girlboss bride parading as a feminist. Sunglasses or not, she is still submitting to an institution that has single-handedly sustained heteronormativity for centuries now, albeit in her “own way”. Just how far can her wedding-day deviance take her? Are her wedding-day glories any guarantee that her marriage will indeed be a site of feminist liberation? At work, she is probably as capitalist as any other patriarchal boss. If not, she probably has to work for a capitalist corporation to fund her feminist wedding. Or worse, her wealth may not even be her own. The idea here is not to diss the girlboss bride but to remind ourselves of the severe limits of this kind of feminist assertion. Would a Dalit woman ever be allowed to ride a horse to a wedding? Unlikely when Dalit men are still being pulled down from horses and beaten by oppressor caste groups.

Marriages remain rigidly patriarchal in India, allowing little or no agency to women and sometimes not even men. Family members arrange up to 90% of marriages. According to data, as many as 1.5 million underage girls are forced into marriage each year and 13,965 instances of dowry-related deaths were registered in 2020 alone. In January, Priyanka Chopra released a video on Instagram talking about her mangalsutra with the director of the Italian luxury brand that designed it for her.

“As a modern woman, I also understand the repercussions of what it means. Do I like the idea of wearing mangalsutra, or is it too patriarchal? But at the same time, I am that generation that’s sort of in the middle. Right?... Maintain tradition but know who you are and what you stand for. And we’ll see [what ]the next generation of girls might do differently.”

All the earnest potential of Chopra’s statement is defeated because the whole thing is ultimately just an ad for a mangalsutra that would cost a whopping 3.49 lakh rupees. Neither its price tag nor the “modern woman” who wears it can change the fact that the mangalsutra is a mark of patriarchal matrimonial servitude.

In September, Bollywood actor Alia Bhatt featured in an ad for a bridal wear brand. Much like the celebrity couple who applied sindoor to each other, the ad made a statement against the Hindu practice of “kanyadaan” and suggested a progressive alternative called “kanyamaan” instead, where parents of both the bride and the groom would “give away” their children in marriage, breaking the custom of the bride being given away by her family.

The proliferation of the girlboss bride trend is definitely a sign that young women are increasingly aware of the patriarchal nature of marriage. But it seems they are comfortable embracing the institution as long as they are allowed to be girlboss brides. A trend that gets co-opted by the capitalist marketplace loses whatever honest intent it might have had to begin with. Brands are always keen to leech off of the progressive intent of consumers. As Andy Zeisler points out in her book We Were Feminists Once, the “empowertising” of marketplace feminism is about branding feminism as an identity that everyone can and should consume. While this isn’t in itself a bad thing in theory, this rebranding, Zeisler writes, highlights only the most appealing feature of a multifaceted set of movements and “kicks the least sensational and most complex issues under a rug and assures them that we'll get back to them once everybody's onboard."

The girlboss bride represents what we wish to see and what the market wishes people would buy instead of what things really are and what people really need.