NOTE: The term "women" is used for analytical clarity of mainstream culture and does not reflect an endorsement of the gender binary. We recognise gender as non-binary and expansive. "Sad-girl" is used as a mainstream label, which is infantilising when "girl" is used interchangeably to mean "woman."

Women’s sadness is portrayed with a pervasive focus on beauty in the dominant culture, exploiting their pain for aesthetics. It is dressed up, staged, framed in soft light, mascara smudged just enough to be beautiful. We grew up seeing it everywhere, in the sad, fainting women in oil paintings, in the wistful eyes of actresses, in songs that found poetry in heartbreak. Somewhere between tragedy and tenderness, women’s sorrow became a performance, something to be admired, rather than understood.

It’s all languid faces, trembling lips, and a silent stream of tears. The sad girl aesthetic pays little regard to what lies behind the emotion—melancholy, grief, horror, or rage—flattening and moulding all pain into something benign and pleasant to the patriarchal voyeur. We’ve been shown this version for so long that we’re conditioned to expect women to perform it in real life. No wonder they feel the pressure to turn their pain into something graceful, something benign that can be objectified. After all, they have constantly been told that their tears matter most when they shimmer. The authentic emotion has to be pushed aside and replaced by the version that looks better from the outside, feeding the misogynist claim that women’s pain is just an innocuous performance.

The Monetisation of the Sad Girl

Singer-songwriter Lana Del Rey ushered an entire generation of Tumblr-era teenagers into the ‘sad-girl’ aesthetic in the early 2010s. Her track , Pretty When You Cry I (2014) became an anthem of that era. This song turns quiet heartbreak into something hauntingly tender. From the very beginning of her career, Del Rey leaned into a dreamy kind of melancholy with her slow songs, soft vintage visuals, and lyrics that made heartbreak cinematic. For many listeners, Del Rey made sorrow feel comforting in a way that was beautifully mysterious, almost alluring, like flipping through faded photographs.

In Del Rey’s music video for the track Summer Time Sadness (2012), a woman jumps off a cliff, another jumps off a bridge as she croons through flickering, blurry images, always looking pretty. Being deadpan or even dead is presumably amazing as long as it all looks beautiful.

Though Del Rey didn’t invent the sad girl, she inherited it, played with it, and made it her signature. Notwithstanding its roots in centuries of oppression, coded in beauty, passed down like an heirloom we never asked for but somehow keep polishing. More than six decades before Del Ray’s video in 1947, Life magazine published the photograph of what is called “the most beautiful suicide.” Robert Wiles took a photo of 23-year-old Evelyn McHale, who died of suicide by jumping off the Empire State Building and landing on the hood of a limousine.

Tumblr-Era Moodboards and the Revival of Melancholic FemininityThe aesthetic inspired by Lana Del Rey’s Born to Die (2012) era appeared in Tumblr moodboards with its own templates: pale sunlight, smeared mascara, cigarette smoke curling like a halo. The filters, bruised hearts, girls leaning out of car windows, and text posts about loneliness read like fragments of poetry. The tags going around were “summer time sadness,” “Hollywood sad girl,” “born to die,” and “tragic beauty.” For many women, the Del Rey sadness was about power in vulnerability, “the opposite of cool girl feminism.” The singer herself called her music “Hollywood sadcore.”

The trend is going strong today. #Sadgirl has exploded with 23.1 billion views, according to Urlebird, a TikTok hashtag tracker. Women are talking about their most intimate pain, but with “an aesthetic that plays with codes of luxury and disarray” where “she cries, but in Chanel,” marketing expert Stéphanie Jouin writes. Never mind that the labels “sad” and “girl” trivialise women’s trauma and infantilise them.

Long before social media and Del Rey, the visual trope of the sorrowful, fragile, hauntingly beautiful women was being painted by artists in the nineteenth century. John Everett Millais’ Ophelia (1851–1852) was inspired by Shakespeare’s tragic heroine of the same name. The painting shows a young woman suspended between life and death, drifting through a river with flowers scattered around her. Her expression is vacant, her body almost weightless, and the entire scene transforms her despair into this soft, lyrical, and strangely serene. Art historians often note that Ophelia “dies while still very young,” her grief romanticised rather than understood.

Cinema picked up the thread, the camera lingering, the light softening when a sad woman appeared. Even the silence feels rehearsed, as if a falling tear itself has to earn its place by catching the light just right, women’s faces breaking apart in perfect light. Think Audrey Hepburn in Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961) or Scarlett Johansson in Lost in Translation (2003).

The sad girl has never just been about sadness. It has always been about control. The ideal woman is young, White or fair-skinned, thin, and quiet, and her problems are small enough to be beautiful but never large enough to demand real relational or structural change. The aesthetic tells us it’s fine to cry over a lost love, but not to rage against injustice. Fine to wilt like a flower, but not to grow thorns. Raging or protesting would be madness, too ugly and dangerous. When things get unbearable, withholding everything, women may die, though without a fuss and still looking pretty in rigor mortis.

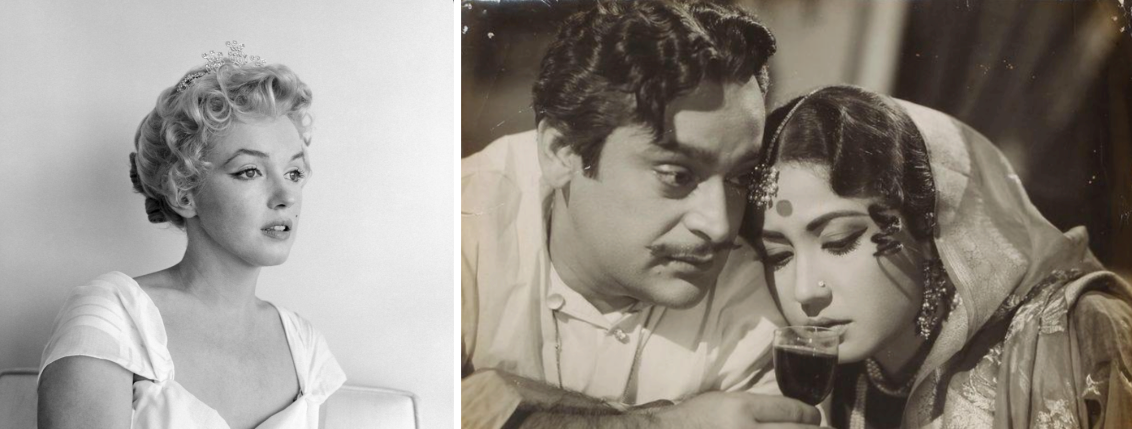

Both Marilyn Monroe and Meena Kumari became mythic emblems of tragic beauty, their on-screen personas and real-life struggles and deaths fusing into enduring cultural archetypes of sorrowful, beautiful women. Monroe’s public persona blurred vulnerability with desirability, her emotional fragility repeatedly staged as charm, even as her real-life isolation and death were absorbed into the same tragic mythology. Meena Kumari immortalised the melancholy woman as Choti Bahu, the wife of an emotionally unavailable feudal lord in (Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam, 1962) and Nargis, the outcast courtesan who dies in a cemetery birthing her daughter, Sahibjaan (Pakeezah, 1972).

Religion and the Indian Script of Stereotype

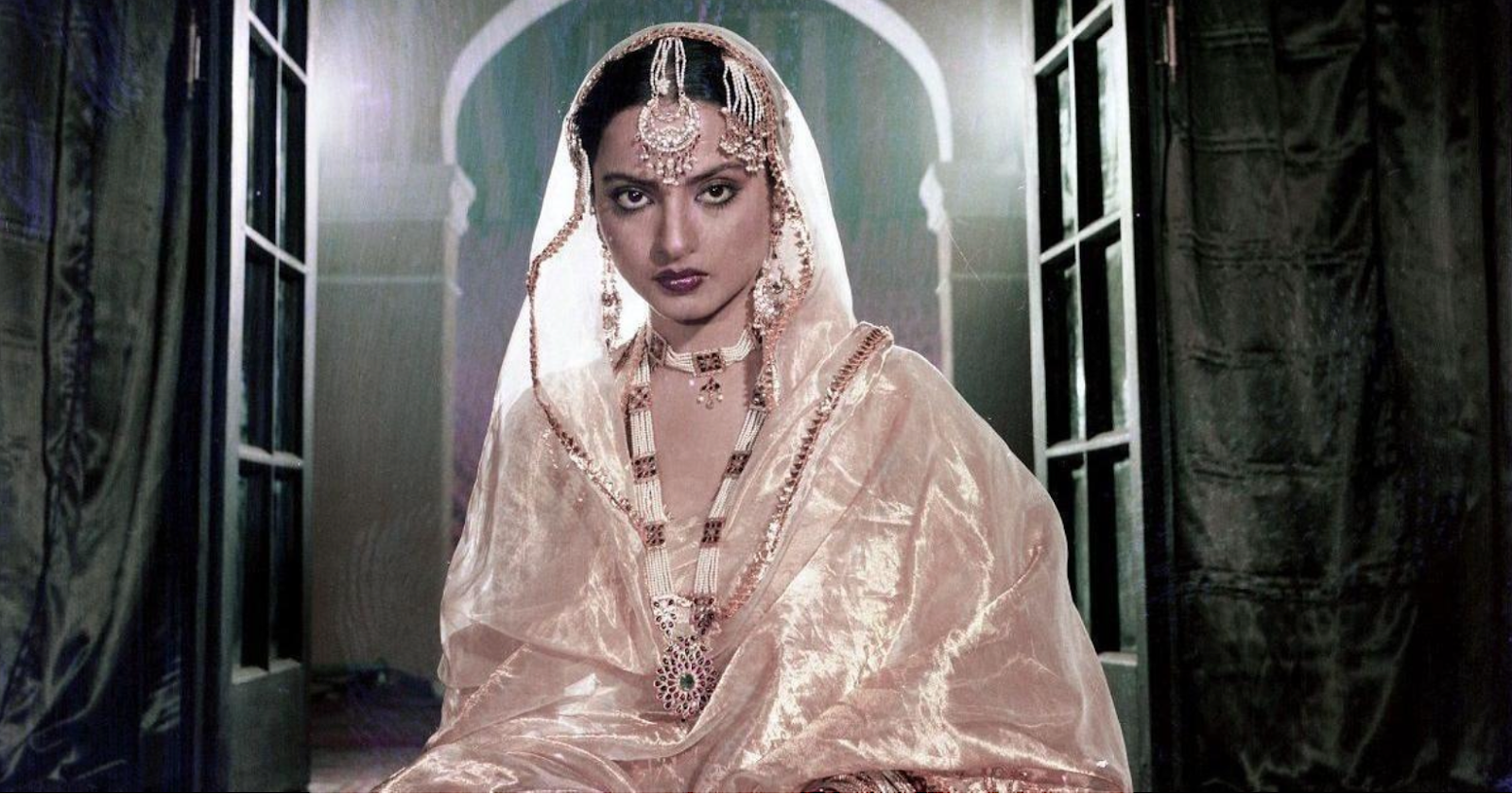

In mainstream Indian Hindi cinema, religious identity has had its own way of choreographing stereotyped identities. The Muslim woman appeared in rigid templates: either hidden and obedient, or excessively bold and sensual. The brothel keeper was almost always written as an older Muslim woman, 'Rashida Bai,' 'Aapa,' 'Khala', her faith turned into cinematic shorthand for moral decay, disqualifying her from the sad-girl aesthetic. The courtesan was allowed to be beautiful, sad, and illicit, therefore doomed to tragic ends.

The Christian woman was mostly scripted as “modern,” wearing revealing clothes, sipping wine, the side character or vamp with dubious morals, often comic, speaking broken Hindi. Her sadness was rarely given canonical weight. Dominant Indian culture keeps oppressed caste women away from the sad girl aesthetic. Especially those who are darker-skinned, have unstyled hair, and wear everyday clothing are framed as too ordinary to be portrayed as subjects of desire.

The domestic worker or the vegetable seller is always the background noise to someone else’s story. The soft-focus is not for her. Simply acknowledging her sadness would shatter the sanitised tranquillity of an ethos where dazzling and presumably virtuous upper-caste women render unnamed injustices invisible.

Films like Shyam Benegal’s Ankur (1974) brought more realness associated with women’s pain. Laxmi, the character played by Shabana Azmi in Ankur (1974), is a young Dalit domestic worker whose physical and sexual labour is exploited but whose humanity is ignored. Her wailing is real and heartrending, exposing the brutality of casteist exploitation of women. In Mirch Masala (1985), Sonbai, played by Smita Patil, joins other women in the chilli factory to resist sexual harassment.

Not Crying Prettily

Why can’t the sad woman still exist, but on her own terms? Not as a fragile ornament, but as someone whose tears are not for show, whose heartbreak is not a performance. When we strip away the beauty filter, what’s left isn’t something less. It’s something real. And that, maybe, is worth more than all the shimmering tears in the world.

Recent films are breaking away from the passive, ornamental sorrow of earlier decades with characters carrying their pain with agency. In Piku (2015), Deepika Padukone plays a woman whose exhaustion, tenderness, and frustration are portrayed without being overtly glamourised. In Queen (2014), Kangana Ranaut’s Rani transforms heartbreak into self-discovery rather than sacrifice. On Instagram, Mangoe Lane takes a look at how Rituparno Ghosh’s work explores women’s trauma with greater nuance.

Maybe the rebellion starts small, letting the mascara run in audacious streaks as the sob twists the face, because real pain isn’t photogenic. It is supposed to be inconvenient and ugly, maybe even a little frightening.