Content warning: Murder, Suicide, Violence

When one of the partners in a famous heterosexual couple dies, women are often pronounced guilty by default and men casually absolved.

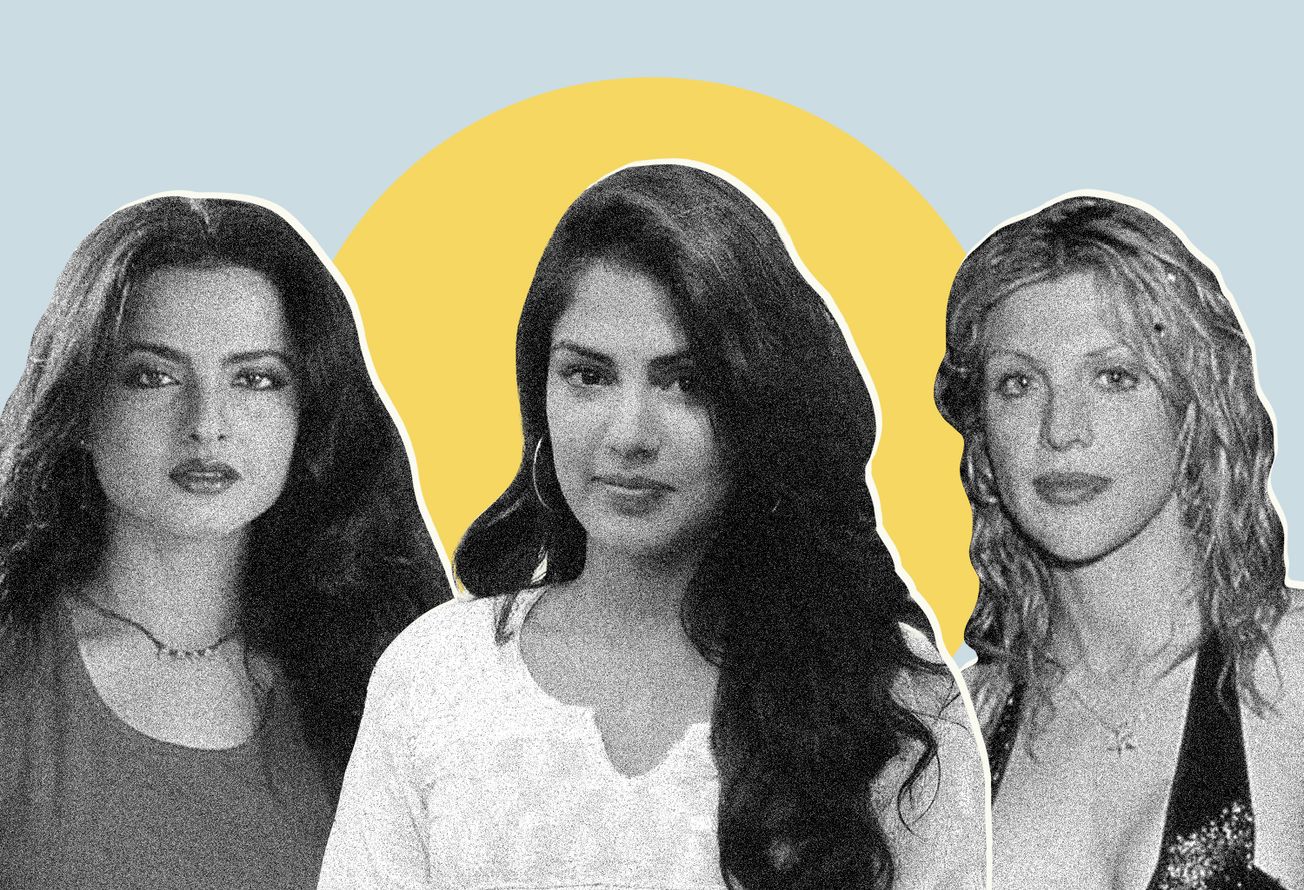

When the twenty-seven-year-old American singer-songwriter Kurt Cobain died of suicide in 1994, it led to a barrage of conspiracy theories blaming his wife, the singer-actor Courtney Love, for his death. A sensational docudrama Soaked in Bleach (2015) made dubious claims about Cobain’s death not looking like suicide and everything pointing to Love as a suspect. She was vilified as a dangerous opportunist; he became the victimised god figure. These are misogynistic distortions of their story.

Not just Love but several women in highly-publicised heterosexual relationships have been blamed for their partners’ deaths— especially when suicide is involved. This happens with outrageous consistency. However, few questions are asked when a woman in a similar “high profile” hetero couple dies. This is despite the overwhelming evidence that men perpetrate intimate partner violence against women everywhere. According to the United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime, every eleven minutes, a woman or girl is killed by her intimate partner or other family member.

Love is an established name in the grunge music scene with Grammy and Gold Globe nominations to boast of. As lead vocalist of the alternative rock band “Hole”, she has released successful albums like Live Through This (1994) and Celebrity Skin (1998). She was described as one among “a whole new breed of angry, funny, complicated women rockers with attitudes”. But women rockers with attitude aren’t treated like men rockers with attitude.

Love was sexually assaulted in a concert in Glasgow in 1991 and wrote a song called "Asking For It" about it. She had stage-dived into the crowd and described what happened in an interview: "[I]t was like my dress was being torn off me, my underwear was being torn off me, people were putting their fingers inside of me and grabbing my breasts really hard." Stage-diving or jumping from the concert stage onto the crowd is practised frequently by male performers.

In 2005, the Creative Artists Agency, an influential talent agency in Los Angeles, banned Love for speaking out against producer Harvey (twelve years before the accusations of sexual assault and harassment against him led to the online #MeToo movement). Assertive woman don't have it easy in the American film and music industry.

The Indian film industry has its share of similar ghastly stories of misogyny and sexist double standards. In 1990, when actor Rekha’s businessman husband Mukesh Aggarwal died of suicide, there was a witch-hunt-like campaign against her. Actor Anupam Kher said she was the “national vamp” and the film magazine Showtime (November 1990) ran a headline that called her “The Black Widow”. “Rekha has put such a blot on the face of the film industry that it’ll be difficult to wash it away easily,” claimed filmmaker Subhash Ghai (who was accused of sexual harassment by actor Kate Sharma in 2018). Aggarwal’s mother was in the headlines for saying, “Woh daayan mere bete ko kha gayi” (That witch devoured my son.)

More recently, when the actor Sushant Singh Rajput committed suicide, his girlfriend, Rhea Chakraborty was accused of killing him with her “black magic.” Media reports were on a roll, calling Chakraborty “gold digger” and “vishkanya” (poison girl) and brandishing sensationalist headlines such as “Love, Sex, Dhokha” (love, sex, betrayal). A woman television host asked, “What sort of web had Rhea Chakraborty spun to suffocate Sushant’s life?”

What is this, if not witch-hunting? When famous men die of suicide, the only acceptable narrative is that their women partners must have caused their deaths, or worse, killed them. Women’s suicides are simply stories of sad, weak, waif-like figures putting an end to their lives. The assumptions being made—suicides are cowardice and fewer men end their lives compared to women—are ableist and inaccurate.

And where is the mass indignation when women in high-profile relationships die in dubious circumstances? When actor Parveen Babi died, none of the men she had accused of assaulting her were considered worthy of suspicion or held responsible for the deterioration of her mental health. Her accusations were dismissed as figments of a "crazy" woman's imagination. Silk Smitha (actor and dancer Vijayalakshmi Vadlapati) committed suicide in 1996. Her handwritten suicide note blaming men in her life of exploitation and betrayal was declared “undecipherable” and the case was closed.

Divya Bharti fell from a fifth floor balcony, Jiah Khan was found hanging, and Sridevi died of accidental drowning in a hotel—their partners weren't hounded and shamed publicly.

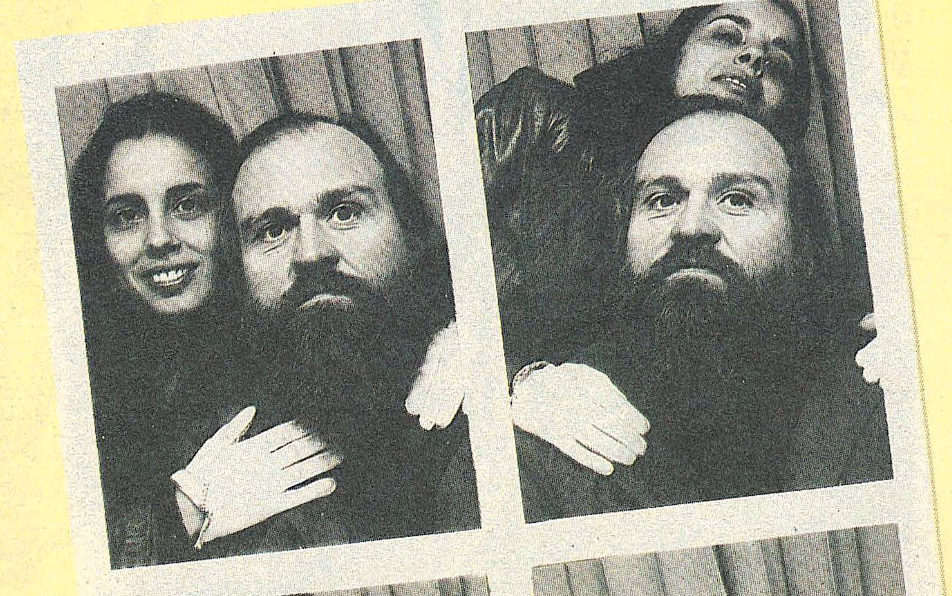

In 1983, feminist artist Ana Mendieta “went out of the window” of the thirty-fourth-storey apartment that she shared with her husband, the sculptor Carl Andre. He was charged with second-degree murder based on the scratch marks found on his face and a doorman’s claim of hearing a woman screaming “no, no, no”. It was known that Mendieta faced domestic violence though it was described as just another couple “drinking and fighting”. Yet André continues to be a celebrated artist. Mendieta’s rich body of work that dealt with the themes of violence, rape, and death is time and again forcibly read as a premonition of her death. Andre’s supporters have expounded on the image of a volatile female artist and pitted it against the myth-making of male genius. Instead of focusing on the actual physical evidence related to Mendieta’s death, art experts and critics were brought into the court trial to elevate Andre’s stature as a “modern master” and relegate Mendieta’s work as reeking of “violence, voodoo, and death wishes.” The court found Andre "not guilty".

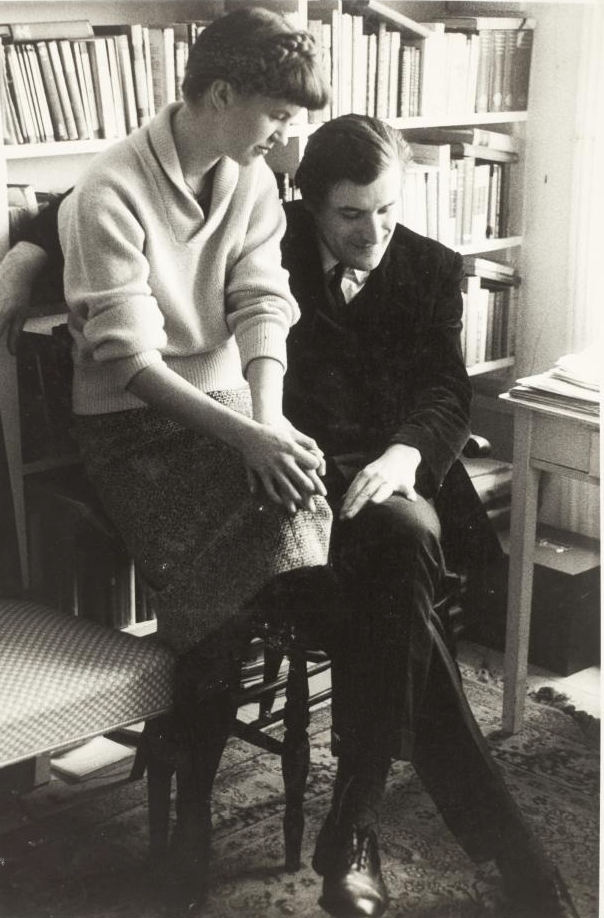

Poet and writer Sylvia Plath also died of suicide in 1963. Her husband, poet Ted Hughes, far from being seen as responsible in any way, was framed as the long-suffering husband of the mentally ill and incurable poet-wife. Plath’s revealing letters to Dr Ruth Barnhouse, her friend and psychiatrist, described the physical and emotional abuse Hughes had subjected her to. Hughes had posthumously edited Plath’s work and profited from her intellectual property. In the foreword to The Journals of Sylvia Plath (1982), which he is known to have “heavily abridged,” he confessed to burning her private journals containing entries made within three days of her death.

Six years after Plath’s suicide, Hughes’s new partner also died of suicide. Asia Wevill was a translator, and advertising copywriter whose relationship with Hughes led to his separation from Plath. Wevill was seen as a home-wrecking temptress and was largely written out of history. Hughes continued to flourish in his career.

The misogynist desire to absolve men of their partners’ deaths is so outrageously obstinate that even a confession to murder won’t sway people. In 1980, Parisian Marxist philosopher Louis Althusser confessed to strangling his wife, Hélène Rytman, a sociologist and anti-Nazi revolutionary overshadowed in life and death by her husband. Althusser went to fetch his friend Dr Pierre Etienne to the crime scene and told him, “I have killed Helen. What will happen now?”

Althusser was later absolved by the French courts on the grounds of insanity. In his posthumously published memoir, L'Avenir dure longtemps (The Future Lasts a Long Time), Althusser meticulously describes how he murdered his wife. His theory and works continue to be taught in liberal arts curriculums.

In her book on domestic abuse, Indian author Meena Kandasamy writes of Rytman and Althusser’s story:

“He would rationalise it with his theory as suicide-by-proxy. A kind of non-consensual consent. A no meaning a yes. She wanted it. His followers would advance the argument that her body did not show any evidence of struggle. Because he was an intellectual, he had the guile to legitimize the murder. Because he was an influential professor, he could make others stand in his support. Because he had an anti-establishment reputation, even the state absolved him.”

The culture of misogyny protects criminal men and criminalises innocent women. As for the sensational news cycles, they generate a lot of money for the media whilst people behind the stories are dehumanised.

Sudeshna Rana is a writer and poet interested in the intersections of gender, culture, and environment. A recipient of the 2022 South Asia Speaks Fellowship, she is currently writing her first book based on her hometown Dhanbad, the coal capital of India.Instagram: theblackcottoncandy