Image: Left- Mughal portrait of a woman (Source: Pinterest); Centre- Pahari painting of a woman at her bath (Source: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston); Right- Ajanta painting of a woman (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Since time immemorial, the patriarchy has eroticized and regulated women’s bodies in general, and their breasts in particular. Marginalized women’s breasts were taxed in the not-so-distant past, they were policed, exploited, mutilated. Women’s respectability depended on how they showcased their breasts across the social spectrum. Even today, this body part is a site of contention. Breasts are largely seen through the male gaze. Breasts are suggestive, sexy markers of gender in conventional discourse. At the same time, breasts are complex sites of contradiction.

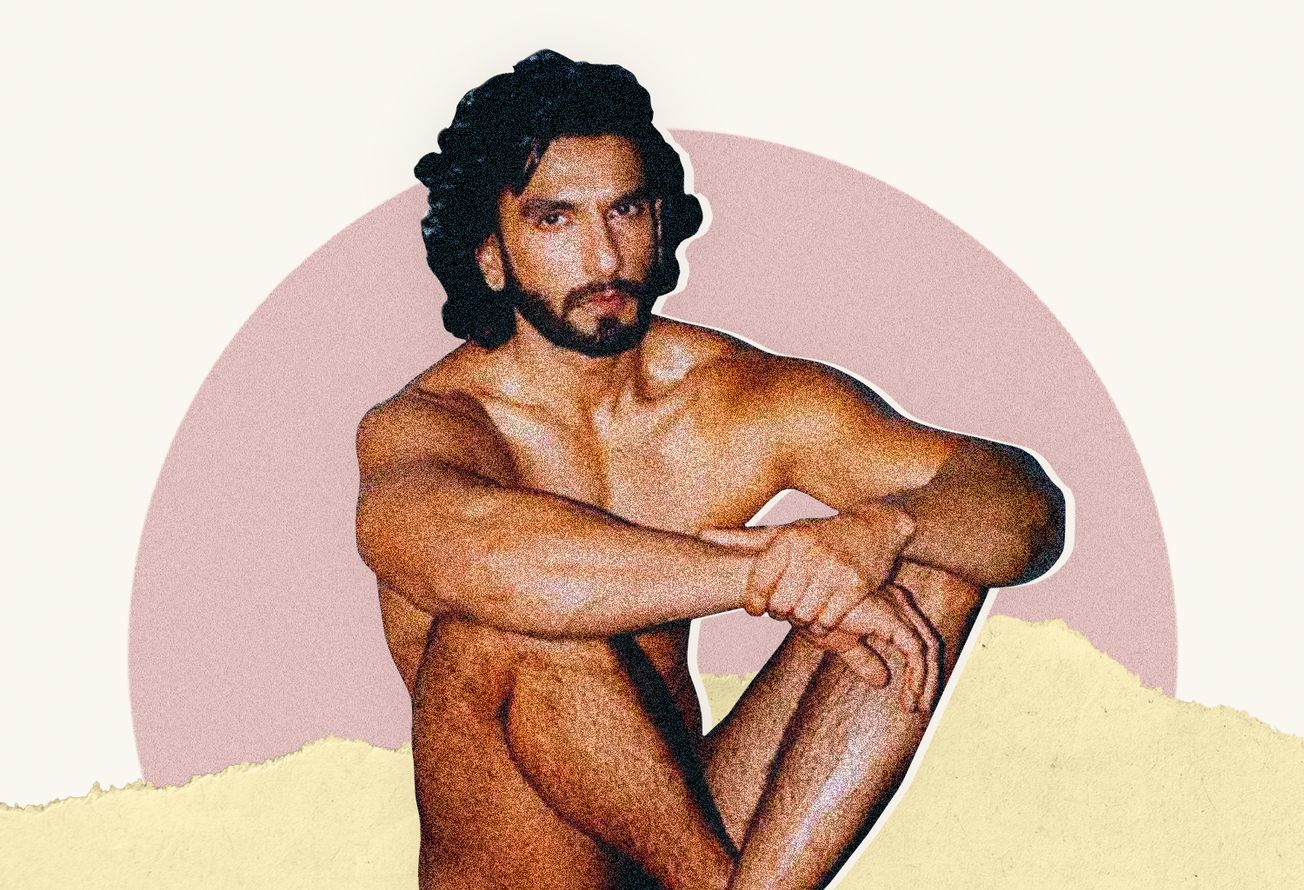

From lovers sucking to infants suckling, breasts portend pleasure, but also, this is where remorse calcifies into pain. They are sites of dysphoria for those of us who are queer. Breasts, or no breasts, each woman contends with them in her own particular way. Women’s breasts then are puzzling pieces of flesh. On the contrary, they are just pieces of flesh hanging from our bodies. Why do we have to go through all that trouble to prop up and cover up breasts in our everyday lives? Why do we have to worry about our breasts being seen. After all, in ancient and medieval India, breasts weren’t exactly hidden from sight. Just a cursory look at sculptures and paintings from that time will expose us to a variety of naked breasts: voluptuous, sagging, bee-stung, conical, flat, adorned with nothing but garlands and jewels. Why are we so scandalized by bare breasts now?

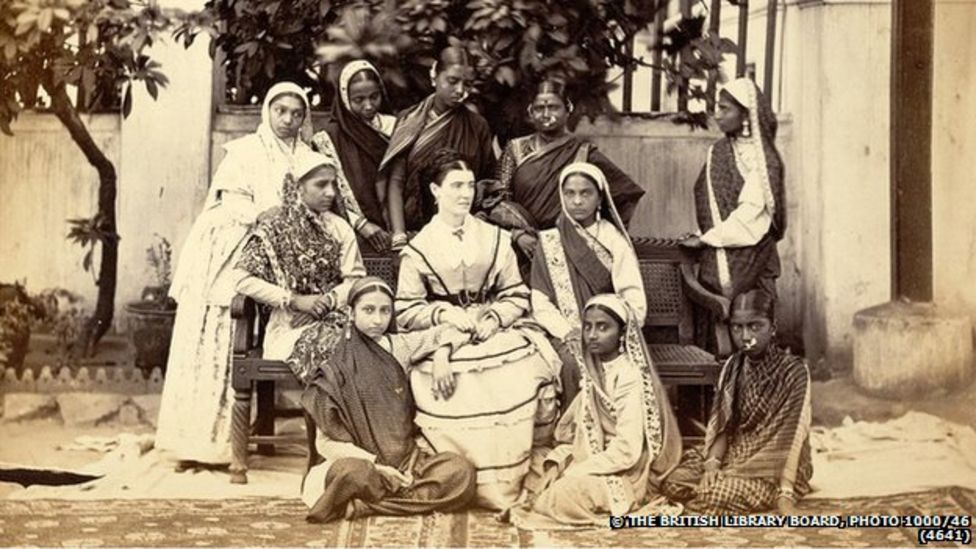

It would seem colonisation has a lot to do with it. It’s a fact that until the 19th century, most Indian women didn’t excessively cover their upper bodies. Sociologist Malavika Karlekar writes that after the middle of the 19th century, female dress reform became an issue, a “movement” among Indian nationalists and intellectuals in Bengal. The style of wearing the sari with a blouse was a western import for the most part. Today, the sari and blouse are believed to be the most traditional attire an Indian woman can wear. The culture police will swear by it. But what will they do when they realize that the most sanskari of outfits was inspired by the British? Will they demand all Indian women wear saris without blouses, because blouses are western?

Breasts are political. Even as colonial India’s caste elite mandated that female respectability entailed covering of breasts, in some parts of the country they simultaneously forbid women of marginalized communities from covering their breasts. The legend of Nangeli, an Ezhava woman from Kerala who cut off her breasts to protest the mulakkaram (breast tax) in 1803, stands as testament to the misogyny and casteism that undergirds Indian society. Nangeli defied the powers that be hundreds of years ago to preserve her dignity. Her breasts were hers to possess, hers to expose, hers to cover—the state had no business regulating her body. She severed her breasts to make that point. Her story of grit continues to resonate even in the 21st century, perhaps because our breasts are still not ours to possess, to expose, to cover. For women from marginalized communities–the inheritors of intergenerational traumas–the memory of indignities perpetrated on their foremothers’ bodies, their breasts, are ever more real, ever more painful. The pain continues to fester in their breasts/our breasts.

So often, we see reports of women’s breasts disfigured by men in fits of rage. They are attacked with acid, amputated, annihilated. Breasts are battlegrounds. They are dangerous sites of violence. This is why we are told to be afraid for our breasts. We are meant to cover up our breasts lest we arouse malevolent males. The cut of a woman’s blouse, the depth of her neckline, the transparency of the fabric that covers her breasts are all potential arousers. So, the more modestly we dress, the more virtuous we are assumed to be. And safer.

Breasts are mammary glands. They are ‘cloudlike breasts raining milk,’ as the Indian epics would put it. Of course, not all women want to be mothers, and even those who are, don’t necessarily breastfeed. But this doesn’t stop the glorification of breasts as sacred mounds of milk and fertility. The irony though, is that even in its role as divine milk jugs, breasts aren’t meant to be seen. Mothers who breastfeed in public spaces are routinely shamed. One time, when a magazine published the image of a woman breastfeeding on its cover, many Indian men found it obscene. They even went to the courts to complain against it. The same Indian men, however, have no qualms about seeing women’s partly bare breasts showcased without infants suckling them.

There’s something inherently perverse about how the patriarchy thinks about breasts. While it freely sexualizes and glorifies women’s breasts in a toxic bacchanalia of misogyny, women themselves aren’t free to do the same. Female desire, after all, is at the margins of India’s popular culture. Here, female eroticism is acceptable only as long as it turns men on. When women express their sexual desires for their own sakes, it is dismissed as ‘their fantasy about life.’ And when women reject the sexualization of their bodies, they’re harassed for non-conformity. There is a deep-seated hypocrisy that girds all sections of Indian society. It’s high time that we ended this bigotry.

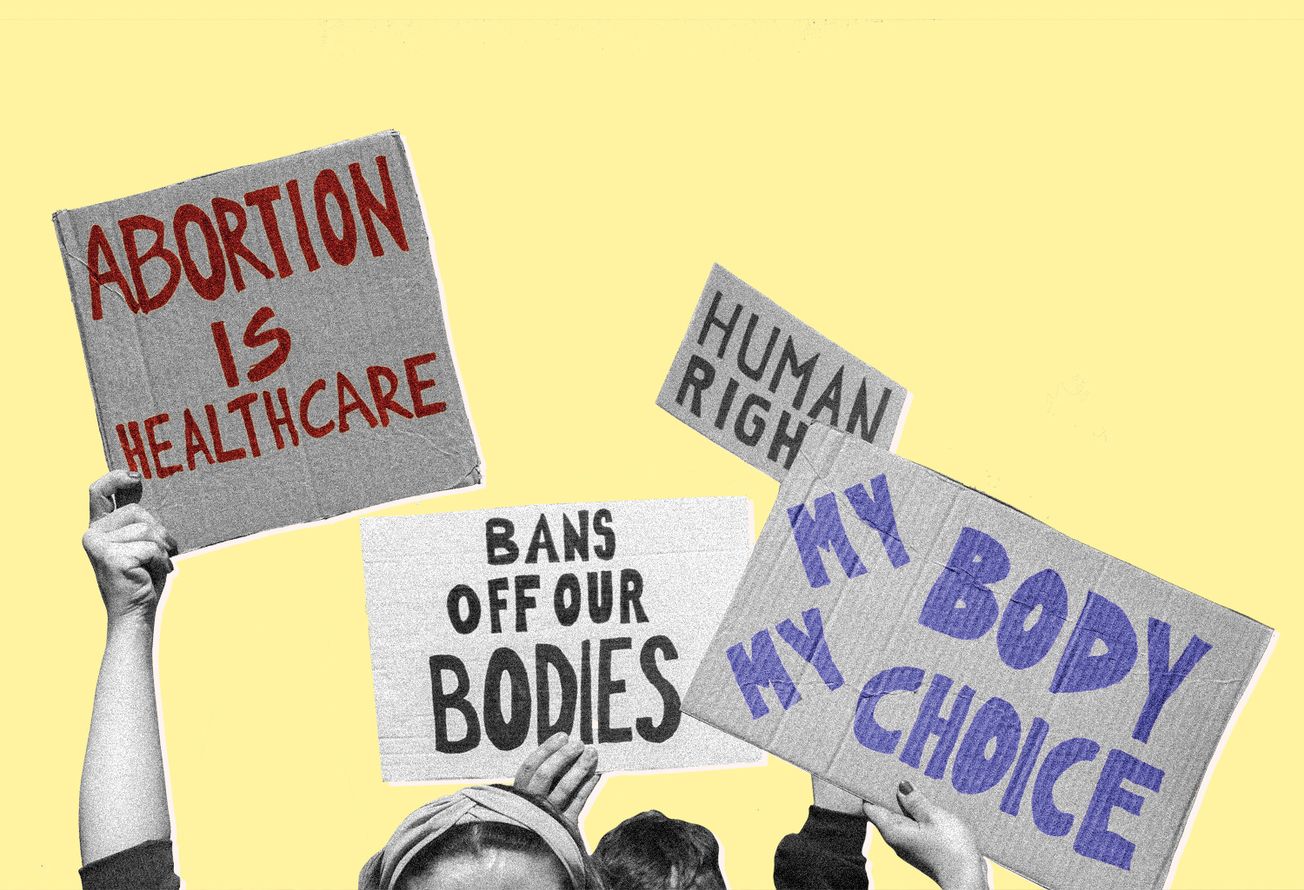

Our breasts are our own. Let us do away with the false dichotomy between good breasts and bad breasts, maternal breasts and concubine breasts, decent breasts and vulgar breasts. Breasts are sexy. Breasts are unsexy. They’re mysterious. They’re exocrine glands. Breasts are breasts. It’s our business what we do with them—whether we flaunt or conceal that cleavage, go topless or wear a niqab, pierce those nipples, breastfeed in public, bind our breasts, or get breast implants—our bodies belong to us. To thrive as women or as people with mammary glands, power and authority over our own bodies is quintessential. So #freethenipple. Free your breast, own your breast, or have it removed.

Disclaimer: The images used in the piece have been credited to the original owners. In case of any copyright violations, please contact Smashboard.