Image Credits: Tazeen Qureshy (Twitter: @TazeenQureshy)

India is the ‘new hotbed of the pandemic’, according to the UN. Only ten vaccine doses per hundred people have been administered in the country. While vaccine mismanagement has contributed to the situation, the disproportionate dependency on technology continues to further curb the access to COVID-19 vaccination for those on the wrong side of the digital divide in India—many in rural areas and some in urban areas with no or limited online access. Many were deprived of essential and critical healthcare such as hospital beds and vaccinations due to this perverse insistence on the use of technology to solve a structural issue in the public health system. On being questioned by the Supreme Court of India on the inefficiencies in the administration of vaccines, the Government of India has asked the court not to interfere in the vaccine policy.

The vaccination drive against COVID-19 began in January, 2021. Despite the fact that gross exclusions have been recorded over the last several years in India’s system of citizen identification, Aadhaar (a 12-digit individual identification number issued by the government) was made mandatory for inoculation. The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare ordered the use of Aadhaar for verifications claiming that it “provides a most reliable authentication of beneficiaries. . .”

The mandatory use of Aadhaar is being touted by some as “not compulsory”, creating confusion and distracting from the need for urgent action to ensure that the 11% of the Indian population that still does not have an Aadhaar are not deprived of the vaccine. RS Sharma, the chairperson of the Empowered Group on Technology and Data Management to combat Covid-19 said that Aadhaar was voluntary. This contradicts the order issued by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Similarly, a supposedly voluntary identification (ID) under the National Digital Health Mission (NDHM) is also underway since the Supreme Court’s directions wouldn’t allow the Aadhaar to be used as a health ID. There have been reports of local authorities declaring this health ID as compulsory. Although, the Government of India, in its recent affidavit to the Supreme Court, has acknowledged the digital divide in the country, the priority continues to be the creation of a health ID and consolidating individual health records into digital systems to further privatise the public health system in the country.

However, creating a health ID would also require the voluntary use of an Aadhaar. Mandating a new health ID created using an Aadhaar recreates the exclusion issues of Aadhaar, further marginalising those already marginalised. There are privacy concerns surrounding the interlinking of health data, especially for marginalised population groups like transgender persons classified under high-risk category for HIV.

The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare release from January 2021 recommends the use of Aadhaar for verification to create Immutable Vaccination Event Records (IVER). In October 2020, Nandan Nilekani, the architect of Aadhaar, proposed a “digital health certificate that can then be shown at a job interview, airport, railway station, bus stand etc.” and that could ensure the administration of the vaccine to all Indians.

What do these trends towards digitizing identity mean for transgender persons, a historically marginalised population group? The Supreme Court judgement in 2018 validating the use of Aadhaar called transgender persons a marginalised group, susceptible to more vulnerabilities and marginalisation. Aadhaar is a mandatory requirement to access HIV treatment. Apprehensions about Aadhaar data breach triggered many people living with HIV to discontinue their HIV medication. The existing discrimination faced by transgender persons as a high-risk group for HIV has further amplified with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, with transgender persons being seen as carriers of COVID-19 virus. Additionally, the nation-wide lockdown during the pandemic took severe toll on the livelihood and the meagre support provided by the government required identification documents in order to access them. Further, people living with HIV+ were reportedly unable to access ART medication during the lockdown due to the fear of revealing their HIV status to people at home. Besides, trans-inclusion in state health insurance schemes is not available across India.

In 2014, the Supreme Court of India recognised the right of every individual to identify as male, female or transgender. Efforts towards establishing a legal framework to protect the rights of transgender persons began in 2015. Good laws protect those they are written for, in this case transgender persons in India. However, despite strong opposition from India’s transgender community to the discriminatory provisions, the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act was passed in 2019. The act spells out the process to be followed by transgender persons who wish to change their identification documents to their preferred name and gender rather than their given name and assigned gender. The process has been digitised ostensibly to protect transgender persons from facing discrimination during in-person visit to government offices. However, the rules continue to demand a pre-existing ID in the trans person’s given name and assigned gender completely undermining the declared intention.

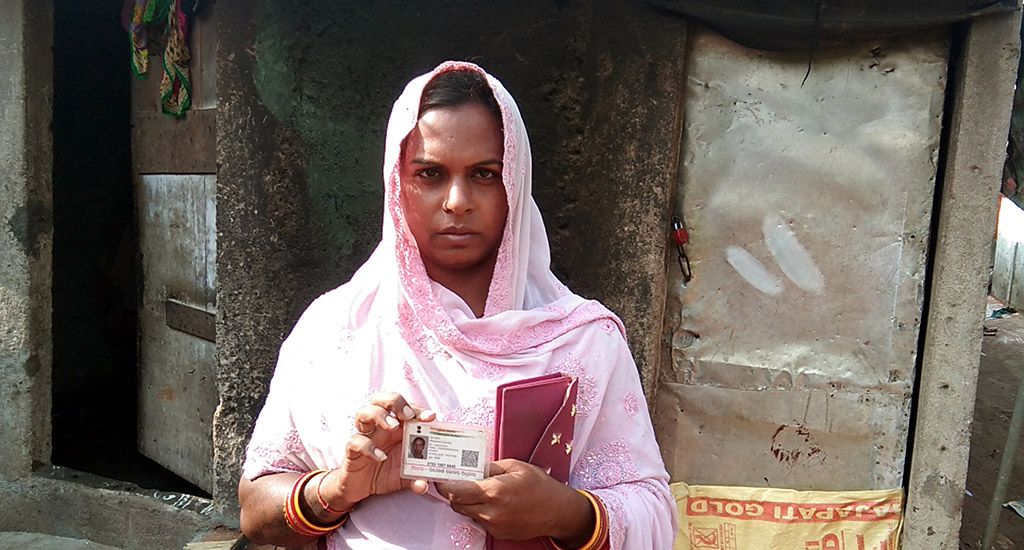

In the study conducted for the Centre for Internet & Society in June 2020, I highlight the common experience of many transgender persons across India—they have to run away from abusive family homes without an identification document in their given name and gender. This deeply impacts their ability to change their name and gender on their identification documents, thereby impacting their access to welfare benefit provided by the state.

Additionally, the access to technology has been crucial to even report domestic violence, which has been on the rise since the onset of the global pandemic. Among survivors home-bound with their abusers, there were many transgender persons as well. According to the UNICEF, a person’s gender identity can prove to be a barrier to internet access, especially in rural India. Clearly the digitisation drive and a law to protect the rights of transgender persons are not able to prevent the exclusion.

The new law hardcodes the identity of transgender persons before and after transitions with digitisation of identification involving a two-step process. This can be a serious challenge for individuals, especially those who self-identify as male or female and not as transgender. Presently, there is no data privacy law in India. Most transgender persons in India don’t have the luxury of accessing or understanding the intricacies of digitisation due to lack of access to the internet and smart devices. Both general and digital literacy among transgender persons runs low in India. Less than 50% have completed class ten according to the National Human Rights Commission 2017 report.

In 2018, the NITI Aayog (National Institution for Transforming India)released a paper on India’s national strategy for the adoption of Artificial Intelligence (AI) extolling its disruptive and potentially transformative power. The study uses the hashtag #AIforAll. However, a serious acknowledgement is required of the gap that exists between this discourse and how the implementation of such strategies affects real people, especially those who face discrimination.

Application of machine learning on large scales of data is crucial for the use of AI. “The measurement, classification and categorisation of any phenomenon into ‘data’ and datasets, which is usable and readable by humans and/or machines, is a task of interpretation which always incorporates human judgements, subjectivities and biases,” says AI Observatory, a project that attempts to critique the dominant narrative of artificial intelligence and data-driven governance in India.

Individuals enter data systems with identification documents carrying different data about them including gender, in order to become eligible to rightfully access their rights and welfare like healthcare, education, food, among others.

The interlinking of different data systems for automated decision-making with no legal framework to address exclusions or privacy concerns, leaves many questions unanswered. What kinds of human judgements and biases will the data of transgender persons capture about them? Will data be captured effectively for all? What about transgender persons who cannot change their identification documents due to one or many challenges that they have always faced? Will all transgender persons still be able to get access to COVID vaccinations? All schemes, including the Trans Act itself, could potentially protect them but they’d still have to first prove that they are transgender with relevant documentation . . . and thus continues the vicious cycle.